|

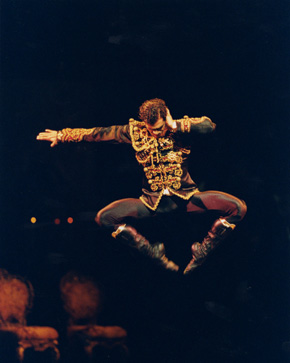

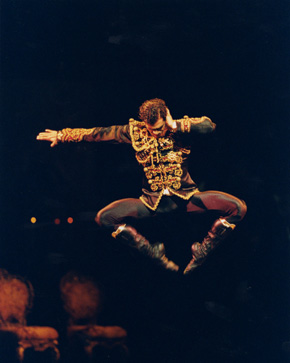

Carlos Acosta dances the

pas de deux for Agon.

It is often said that being admitted into the Royal Opera

House’s inner sanctum is like being on an ocean liner from

the golden age of steam.

This afternoon I am there to meet Carlos

Acosta, the world’s foremost classical ballet

dancer, so it certainly feels this way.

Buzzed in through the stage door entrance

and into a cosy, old-fashioned reception area,

I am led into a labyrinth of narrow corridors

and endless double doors. Aside from the

rehearsal calls for performers and production

staff reverberating over the PA system, there is

a hushed, almost reverential air to the place.

Once inside, time seems to slow and real

life is left behind. It takes an eternity to make

our way to the office where I am to interview

Carlos Acosta, negotiating the lifts and complex

colour-coded floor levels.

It is as if the building itself is a mirror to

the intricacies and traditions that drive

classical ballet.

The Cuban superstar literally hobbles in and wearily sits himself

down. He has only recently had surgery on his foot to repair

floating bones and

is astonished at how quickly his body is recovering.

‘I’m still in pain’, he says matter-of-factly.

‘But surgery and injuries are

a normal aspect of dance.’ He appear slighter than the

muscular form that

gracefully dominates the stage in his performances and lean

in the way

only athletes can be, but the dynamic, alpha-male presence that

Acosta is so

famous for, is definitely there.

‘Our body is our instrument,’ he says, referring

to dancers. ‘But anything

can affect your work and it’s very hard to be 100% all

of the time.’ With

humility, which I later come to realise is typical of Acosta,

he sounds like

any other sportsperson sizing up his performance. However, this

is no

average athlete, and the ‘body’ he refers to, no ordinary

instrument. Wowing

audiences ever since he first emerged onto the

international ballet scene as a teenager, Acosta has

taken what is arguably one of the last bastions of

high art by storm, lending it something real and

very human. He is routinely compared with the

great classical stars Nureyev and Baryshnikov, and

is often described as one of the most influential

dancers of our time.

His story is all the more compelling when you

learn of his impoverished upbringing in the back

streets of Havana, his ambitions to be a footballer

and his father’s insistence that he study ballet to

keep him from fraternising with street gangs.

Artistic expression

For an artist so universally lauded throughout

his career, there is no trace of arrogance or sense

of entitlement about him. He is relaxed, friendly

and open, displaying a wry sense of humour

throughout the interview. He seems happy just to

chat while on a break from his intense rehearsals

for the one-act ballet Winter Dreams.

| ‘ROMEO IS VERY DEMANDING

AND A ROLE THAT DOESN’T

COME NATURALLY TO ME.

I AM POWERFUL AND BIG. I AM

APOLLO AND SPARTACUS.

I’M NOT BOYISH.’ |

We begin with Acosta’s latest undertaking outside of dance.

After three

years in the making, he has just completed his first novel.

A story about the

history of Cuba from the time of slavery to the current day,

it is his first

work of fiction, and follows his 2007 autobiography No Way Home.

‘I’m finished and I’m proud of it, but I never

want to write another word again. My hair is falling out because

of it!’ he jokes. ‘I enjoyed the process, but writing

drains you. I was doing it between breaks in dance rehearsals

and production meetings, so it was tiring. But I am trained

to finish what I start. We’ll see if people like it.’

Indeed, it’s hard to imagine where Acosta finds the time

for all his numerous projects, from writing and staging his

own ballets (the highly acclaimed and successful Tocororo),

to appearing in the feature film New York, I Love You last year

with Natalie Portman, as well as a packed schedule of international

guest appearances and tours.

|

|

Despite turning 37 this year, a time when a dancer might traditionally

contemplate retirement, Acosta is doing nothing of the sort.

‘I need challenges otherwise I get bored,’ he says,

leaning back into his chair, his strong, commanding physique

draped in tracksuit pants and a sweatshirt.

One of these new challenges came in the guise of Premieres,

an experimental, mixed media Sadler's Wells collaboration blending

dance and film, staged at the London Coliseum over the summer.

I ask him if this kind of production is the future of dance.

‘It’s just one aspect of dance,’ he replies,

his English shot through with a rich Cuban lilt, ‘and an

idea that hasn’t been explored much before, so it was interesting

to see the results. Sometimes I succeed in producing something

worth seeing and sometimes I don’t,’ says Acosta,

perhaps referring to the production’s mixed reviews. ‘But

I’m not afraid to explore.’

He goes on, ‘An artist should never be afraid to explore.

In exploring lies the search for a new world waiting to be discovered,

or a new path that hasn’t been taken before. This is how

art and dance evolve.’

Listening to Acosta talk freely about himself and his art is

an almost poetic experience, partly because he avoids convenient,

trite sound-bites and also, I suspect, because there is no PR

present to curb his musings. Something that is both surprising

and refreshing.

Inner drive

Throughout his career, Acosta has danced all the big classical

roles – Giselle’s Albrecht, Siegfried in Swan Lake,

the demanding Spartacus – bringing to them his signature

strength and physicality. But he is brutally honest about how

his familiarity with the roles at this stage in his career has

its limitations artistically.

Carlos Acosta as Prince Rudolph

in Mayerling.

‘I have to ask how I can deliver what I know so well in

a new and interesting way. I need to constantly find other challenges

outside of these classical roles to help me continue with my

career. If the only thing I have to look forward to is the classics,

that would be very boring.’

Acosta’s tireless drive and pursuit of achievement is

tangible. Beneath his disarmingly charming and easy-going manner,

is a steely resolve. It is visible in his eyes when he talks,

an unwavering focus. This is a man who never stops. He goes

on to reveal that part of this inner drive also comes from disaffection

in his life.

‘I find if I have a lot of time on my hands, then thoughts

get into my mind. I don’t like to think. I begin thinking

and I get depressed.’ I ask him if his well-documented

home-sickness for Cuba is at the root of this. He nods sadly,

‘I miss Cuba.

here is a guilt at not being there. But as long as I have new

doors opening for me, then it’s okay.’ Acosta accepts

that his phenomenal success has come at a cost.

A faraway look comes into his eyes, ‘Cuba is a long way

away. It’s not like travelling three hours to Spain. I

have had all this wonderful success, but have not had my family

around me to share in it.’ Our man in Havana In 1991, aged

only 18, Acosta was invited to join the English National Ballet

as a principal by its then director Ivan Nagy. It was the start

of a career working with major ballet companies in Europe and

America, but it also marked the start of prolonged periods away

from his home and family in Havana. In the 1990s, it was extremely

difficult to travel to and from the socialist island nation.

Now, he feels, it is more open and, as an international dance

star, he has the freedom to go back and forth. He tells me about

his big house in Cuba and his future plans to live there with

his English girlfriend.

‘Eventually, I want to help the dance field in Cuba and

be involved in everything that is happening there,’ he

explains. ‘Cuba has been disconnected from the rest of

the world for a long time now.’

Dance is an enormous part of Cuban life, and the huge success

of ballet as an art form in Cuba is deeply entwined with the

revolution itself. Since the political events of 1959, ballet

has been a significant and accessible part of Cuba’s cultural

heritage. Much of this success is attributed to the work of

Cuban national treasure and the Godmother of Cuban ballet, Alicia

Alonso.

Director of the Cuban National Ballet since its official founding

in 1960, Alonso set up the company and its training programme

with considerable financial support from Fidel Castro’s

new political regime. To this day, the Cuban school of dance

is universally recognised throughout the world as exceptional.

|

|

As Acosta explains, ‘The Government was very involved

in ballet from the beginning and gave it the seal of approval.

It formed the schools. Ballet was always on TV. Fidel Castro

himself was always attending ballets.

Everybody in Cuba embraced the idea. After 50 years of this,

what you have is a country very well educated in ballet and

the arts.’ For the time being, Acosta lives happily with

his girlfriend in north London and hopes to start a family here

in the UK in the near future.

However, his yearning for Cuba seems to inform much of what

he does and he envisages a life of commuting back and forth

between the two countries.

‘I have plans to go back to Cuba but also to stay connected

with the UK. It’s a great balance for my life to be in

both countries.’ He has nothing but appreciation for his

adopted home of the past 12 years.

‘Britain, to me, is the best country in the world,’

he says smiling. ‘London is a great city. The British embrace

uniqueness, ethnicity and most of all, talent.

In London, if you are talented, it doesn’t matter where

you come from. If you prove yourself, the sky’s the limit.

The Royal Ballet is proof of this.’

| ‘IN LONDON, IF YOU ARE TALENTED,

IT DOESN’T MATTER WHERE YOU COME FROM. IF YOU PROVE

YOURSELF, THEN THE SKY’S THE LIMIT. THE ROYAL BALLET

IS PROOF OF THIS.’ |

In control

A permanent member of the Royal Ballet in Covent Garden since

1998, Acosta is currently principal guest dancer with the company.

When I ask him what his favourite dance role has been to date,

he says all of them, and reveals a more spirited and playful

side with just a dash of Latin American machismo. He mentions

Romeo and Juliet: ‘Romeo is very demanding, and a role

that doesn’t come naturally to me.

I am powerful and big. I am Apollo and Spartacus. I’m

not boyish. Other people can project that boyishness naturally,

but you see my thighs?’ he says with a puckish grin, pointing

to his celebrated physique.

‘I am really powerful. When I walk on stage you see someone

in control. To try to inhabit those kinds of roles – therein

lies my challenge.’ If Acosta is made for these kind of

macho, superhero roles such as Apollo and Spartacus, then who

better to promote ballet as a vocation to young people, especially

boys? It’s something he is passionate about. ‘In order

to train the kids, you need to educate the parents about ballet

and dance. There is a preconception around ballet and the sexuality

of a male dancer. But dance and ballet is a wonderful world

and will not alter the psychology of a child,’ says Acosta,

referring to the fact that sexuality has nothing to do with

dance.

Carlos Acosta rehearses with

Marianela Nunez for Winter Dreams.

The hard work, athleticism and discipline required to become

a worldclass dancer are well-known, but where does he find his

inspiration? ‘What inspires me most is my audience. It’s

the people who come to my shows again and again. Their recognition

of what I am producing really helps me.’ Acosta has a huge

following and fan base, with his name alone on a billing selling

out shows.

‘I can get inspiration from anything; a book or a painting,’

he explains. ‘The city also really inspires me, as there

is so much good art out there. I want to be able to share in

that elite. It inspires me to be the greatest I can be.’Carlos

Acosta glances at his watch and realises he is late for his

rehearsal.

He gracefully apologises for his outfit and hobbles off again

for more hours of rehearsals and the pursuit of perfection –

a true danseur noble.

|